Can We Trust Hadith Literature? Understanding the Processes of Transmission and Preservation

How has Islamic civilization maintained the rich literary heritage of Ḥadīth developed by early Muslim scholars? What guarantee is there that the collections of ḥadīths in our possession have reached us accurately and that they were compiled by their purported authors? This paper addresses these questions.

Published: October 30, 2018 •Safar 21, 1440

Updated: July 22, 2024 •Muharram 16, 1446

Author: Mufti Muntasir Zaman

بِسْمِ اللهِ الرَّحْمٰنِ الرَّحِيْمِ

In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.

For more on this topic, see Hadith Series

Abstract

Procedures for preservation

Ibn al-Wazīr’s rejoinder

The usage of non-samāʿ copies

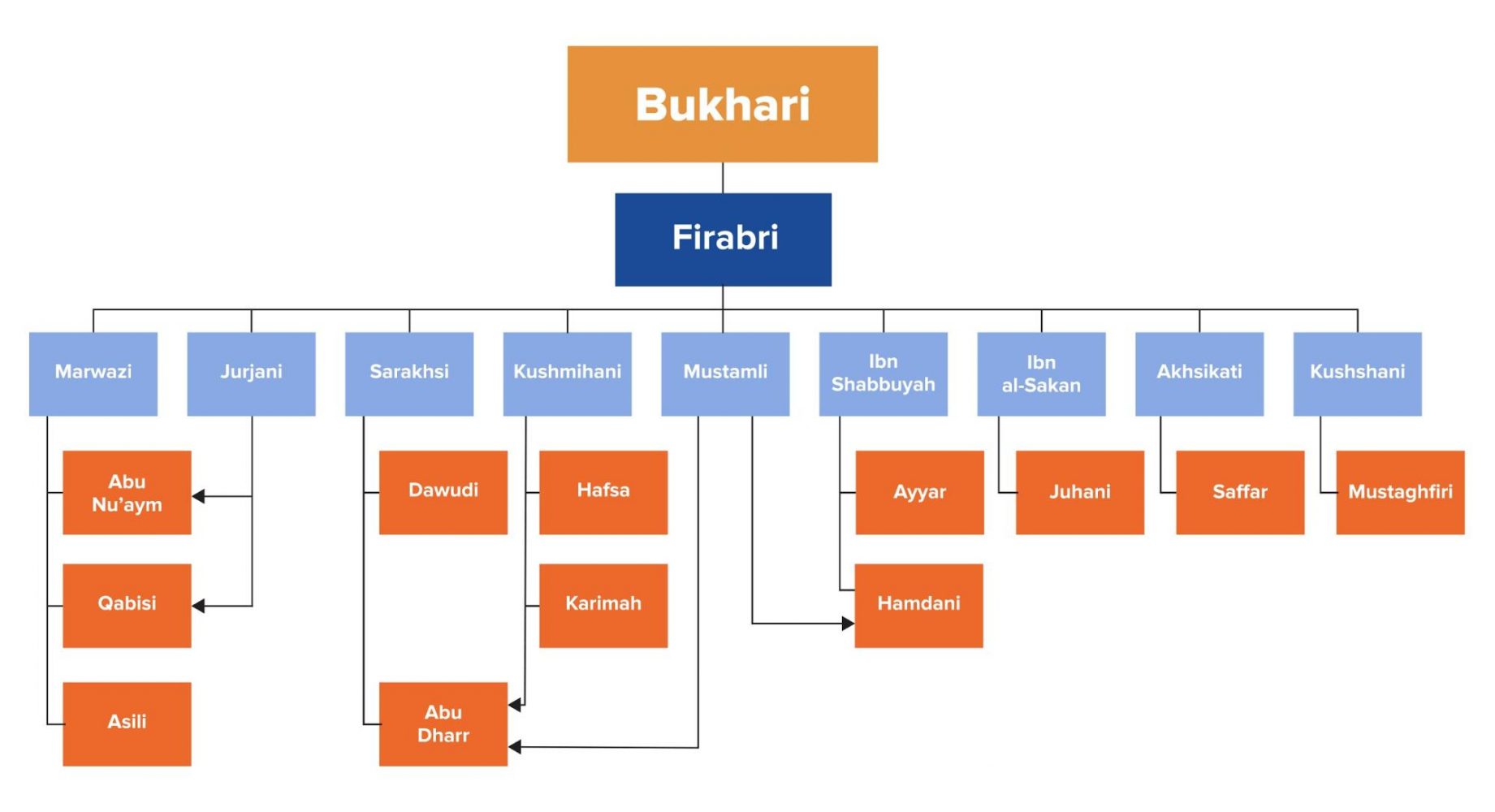

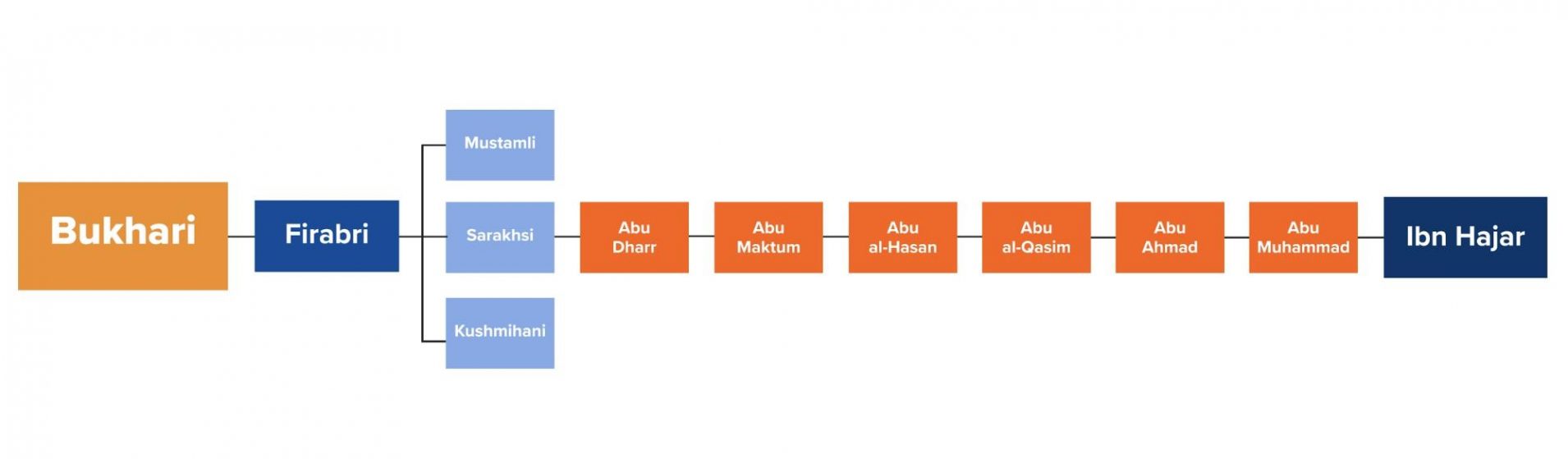

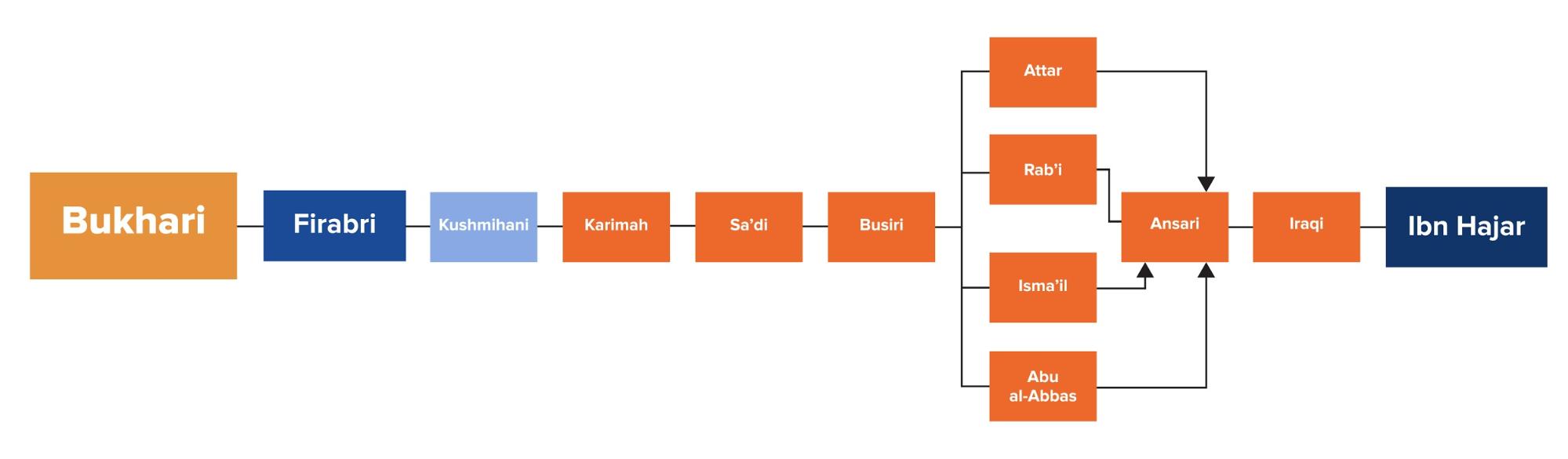

Appendix: Transmission of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī

Notes

1 ʿIyāḍ, al-Ilmāʿ, p. 173; al-Zarkashī, al-Nukat, vol. 3, p. 589.

2 See Ṣaqar, “Introduction,” in al-Ilmāʿ, p. 22. In chapters 24-26 of his Muqaddimah, Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ expands on the subject, and those who wrote glosses on his book further built upon his observations. See Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ, Maʿrifat Anwāʿ ʿIlm al-Ḥadīth, pp. 128-236.

3 See ʿIyāḍ, al-Ilmāʿ, p. 155. Al-Ḥasan al-Saghānī (d. 650 AH), who wrote one of the most reliable manuscripts of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, is noted for his unique style of writing. For instance, beneath the letter sīn, he would write a letter sīn in a smaller font to avoid confusing it with the letter shīn. On al-Ṣaghānī’s style of writing, see Khān, “Introduction,” in al-Murtajal, p. 11; Abū Ghuddah, Annotations on Taṣḥīḥ al-Kutub, p. 28.

4 Many narrators transmitted the Sunan from Abū Dāwūd. The most prominent among them was Abū ʿAlī al-Luʾluʾī (d. 333 AH), who heard the Sunan from its author numerous times, including the year of the author’s demise. From al-Luʾluʾī, Abū ʿUmar al-Hāshimī (d. 414 AH) narrates the Sunan, from whom al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī (d. 463 AH), Abū ʿAlī al-Tustarī (d. 479 AH), and Abū Manṣūr ibn Shakrūyah (d. 482 AH) narrate it. See al-Sakhāwī, Badhl al-Majhūd, pp. 61-66.

5 Ibn Nuqṭah writes that it is nearly impossible for anyone to encompass all the transmitters of Ḥadīth books, so he only mentioned the most prominent among them. Ibn Nuqṭah, al-Taqyīd, vol. 1, p. 130. Taqī al-Dīn al-Fāsī (d. 832 AH) wrote a supplementary work on Ibn Nuqṭah’s book.

6 Other resources for the biographies of literature-transmitters include the athbāt, fahārīs, and maʿājim catalogs, which ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Kattānī (d. 1962) describes in the following words, “mashyakhah is a catalog wherein a Ḥadīth scholar gathers the names of his teachers and his narrations from them. People later began referring to it as muʿjam when they would gather the names of the teachers separately in alphabetical order; thus, the usage of muʿjams gained currency alongside mashyakhas. The Andalusians use the term barnāmaj.” See al-Kattānī, Fahras al-Fahāris, vol. 1, p. 67; cf. ʿAwwāmah, Tadrīb al-Rāwī, vol. 2, pp. 420-21, 564; cf. vol. 4, p. 267 [for the vowelization of these terms, see ibid.].

7 Brown, The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim, p. 62.

8 As will be demonstrated shortly, the shift in scholarly attitude towards the usage of non-samāʿ copies was gradual and did not take effect immediately after the period of canonization.

9 This was carried out mainly through one of three modes: (1) hearing a narrator read/recite ḥadīths aloud; (2) reading a text aloud to a teacher; or (3) being present while a text was read aloud. See Davidson, Carrying on the Tradition, p. 80.

10 Ibn Nuqṭah, Ikmāl al-Ikmāl, vol. 3, p. 283; cf. al-Dhahabī, al-Mughnī fī al-Ḍuʿafāʾ, vol. 2, p. 500.

11 Al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Baghdād, vol. 5, p. 116; Brown, Hadith, p. 43; idem, The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim, p. 62.

12 Al-Ḥākim, Maʿrifat ʿUlūm al-Ḥadīth, p. 88. On the importance Ḥadīth scholars gave to oral/aural transmission, see Abū Ghuddah, Ṣafḥah Mushriqah, pp. 99-102, 144-49; ʿAwwāmah, Maʿālim Irshādiyyah, p. 188 ff.

13 Only 52 folios of this manuscript are available, comprising the chapters of Zakāh, Ṣawm, and Ḥajj, in the Mingana Collection at the Cadbury Research Library. Based on the style of its script and its authorization notes (samāʿāt), the manuscript can be dated either to the lifetime of al-Marwazī or the transmitter from him. See al-Sallūm, “Introduction,” in al-Mukhtaṣar al-Naṣīḥ, pp. 76-77; cf. Blecher, Said the Prophet of God, pp. 5-6.

14 For instance, the chain of transmission for the first ḥadīth in the chapter of Zakāh is, “Akhbaranā Abū Zayd Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad qāl ḥaddathanā Muḥammad ibn Yūsuf qāl akhbaranā al-Bukhārī qāl ḥaddathanā Abū ʿĀṣim al-Ḍaḥḥāk ibn Makhlad ʿan Zakariyyā ibn Isḥāq ʿan Yaḥyā ibn ʿAbd Allah ibn Ṣayfī ʿan Abī Maʿbad ʿan Ibn ʿAbbās anna al-Nabī ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam baʿatha Muʿādh…”

15 Mingana, An Important Ms. of Bukhārī’s Ṣaḥīḥ, in The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 2 (1936), p. 289.

16 Ibrāhīm ibn Maʿqil’s recension is preserved in Abū Sulaymān al-Khattābī’s (d. 388 AH) Aʿlām al-Ḥadīth, one of the earliest commentaries on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, as the author himself explains in the introduction. While commentating, however, al-Khaṭṭābī generally does not cite the ḥadīths in their entirety. See Muḥammad Āl Saʿūd, “Introduction,” in Aʿlām al-Ḥadīth, vol. 1, p. 76. For a handful of narrations of the Ṣaḥīḥ via the recension of Ibrāhim ibn Maʿqil and Ḥammād ibn Shākir found in secondary sources, see Jumuʿah, Riwāyāt al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ wa Nusakhuhū, pp. 145-56, 164-69. The claim that Ibrāhīm ibn Maʿqil’s recension lacks 300 hadīths that are found in al-Firabrī’s recension is an exaggeration. Dr. Shifāʾ al-Faqīh estimates that the number is 46 ḥadīths. See Shifāʾ, Riwāyāt al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ li al-Imām al-Bukhārī, pp. 62-65; al-Sallūm, “Introduction,” in ʿAdad Jamīʿ Ḥadīth al-Jamīʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, pp. 16-17; Mutawalli, Ziyādāt, p. 26.

17 Al-Sallūm, Risālah fī Radd Shubah Minjānā, pp. 9-10. The cited reference is an appraisal of Mingana’s criticisms in An Important Manuscript of the Traditions of al-Bukhārī; cf. Brown, The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim, pp. 384-386.

18 Konrad Hirschler, The Written Word in the Medieval Period, p. 32 ff.

19 From the 5th century AH, details of auditions were systematically documented. In addition to the names of the attendees, the date and venue of the audition and the state and sitting arrangements of the audience were noted. See Davidson, Carrying on the Tradition, p. 87.

20 A total of ninety sessions were held for the 8th volume (i.e., sessions no. 527-617), it was completed on 15/16, Jumādā al-Ūlā, 634 AH, the venue was Dār al-Ḥadīth al-Ashrafiyyah in Damascus, and the registrar was ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAlī al-Dimashqī. See the addendum to the 8th volume of al-Sunan al-Kubrā [Hyderabad Deccan edition], pp. 346-50; cf. Abū Ghuddah, Ṣafḥah Mushriqah, p. 103.

21 See al-Qasṭallānī, Irshād al-Sārī, vol. 1, p. 40; cf. Zuhayr Nāṣir, “Introduction,” in al-Jāmiʿ al-Musnad al-Ṣaḥīḥ, pp. 36-39. Ibn Mālik’s Shawāhid al-Tawḍīḥ wa al-Taṣḥīḥ li Mushkilāt al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, a grammatical exegesis of difficult passages in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, was an outcome of this reading session. For a study of al-Yūnīnī’s manuscript of the Ṣaḥīḥ, see Jumuʿah, Riwāyāt, p. 663 ff.

22 See al-Kattānī, Fahras al-Fahāris, vol. 1, p. 198; ʿAwwāmah, “Introduction,” in Sunan Abī Dāwūd, pp. 99-103.

23 Ibn al-Wazīr, al-ʿAwāṣim wa al-Qawāṣim, vol. 1, pp. 302-4. Also see Motzki, The Question of the Authenticity of Muslim Traditions Reconsidered: A Review Article, in Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins, pp. 242-44.

24 See al-Burzulī, Jāmiʿ Masāʾil al-Ahkām, vol. 1, p. 79.

25 Al-Zarkashī explains that scholars were more meticulous in their treatment of Ḥadīth manuscripts than any other genre, including books of Islamic law. See al-Suyūṭī, Tadrīb al-Rāwī, vol. 1, p. 572.

26 Ibn al-Wazīr, al-ʿAwāṣim wa al-Qawāṣim, vol. 1, p. 306.

27 Ibn al-Wazīr explains that a sign that the major Ḥadīth books have not had texts interpolated is the absence of politically or theologically motivated forgeries in an authentic compilation like Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī that would have granted them the status of authenticity. See Ibn al-Wazīr, al-ʿAwāṣim wa al-Qawāṣim, p. 306. In a similar vein, the fact the Ḥadīth compilers cited defective chains is an indication that they did not fabricate the reports they transmitted. In the case of the Muwaṭṭaʾ, for instance, Harald Motzki explains, if Mālik was fabricating Prophetic ḥadīths to support his positions, why would he then quote the opinions of al-Zuhrī and not project them also as Prophetic reports? Furthermore, if Mālik—as well as the other compilers—forged the ḥadīths in the Muwaṭṭaʾ, why would he cite broken chains of transmission for certain ḥadīths and not embellish them as continuous chains? This demonstrates that they were reliably transmitting what they heard from their informants. See Motzki, The Jurisprudence of Ibn Shihāb az-Zuhrī: A Source-critical Study, pp. 21-22. For an answer to a potential objection to this line of reasoning, see al-Aʿẓamī, Studies in Early Ḥadīth Literature, pp. 219-22.

28 Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ, Maʿrifah Anwāʿ ʿIlm al-Ḥadīth, p. 17. Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ’s concerns regarding the grading of ḥadīths that were not graded by earlier scholars due to the unsatisfactory state of the transmitters are to be understood in reference to rare Ḥadīth collections (ajzāʾ) that were not adequately transmitted, not the major books of Ḥadīth. For more on this, see ʿAwwāmah, Annotations on Tadrīb al-Rāwī, vol. 2, p. 539 ff.

29 Al-Zurqānī, Sharḥ al-Muwaṭṭaʾ, pp. 5-6; Ḥamdān, al-Muwaṭṭaʾāt, pp. 77-84. For a more exhaustive list of transmitters, see al-Aʿẓamī, “Introduction,” in al-Muwaṭṭaʾ, pp. 188-250.

30 Al-Dhahabī does not accept the authenticity of al-Firabrī’s statement, “90,000 people heard the Ṣaḥīḥ of Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl, and no one besides me remains who transmits it from him.” See al-Dhahabī, Siyar, vol. 15, p. 12. Shaykh ʿAwwāmah explains that his critique is unwarranted. See ʿAwwāmah, Annotation on Tadrīb al-Rāwī, vol. 2, pp. 365-66. Ṣāliḥ Fatḥī writes that the words al-Dhahabī used here are “wa lam yaṣiḥḥ (it is inaccurate),” which is not a criticism of the chain of transmission for the statement; rather, he disagrees that Firabrī was the last to transmit the Ṣaḥīḥ. See Ṣāliḥ Fatḥī, Nuskhat Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī al-Aṣliyyah wa Ashhar Riwāyātihī, Majallat al-Turāth al-Nabawī, vol. 1, no. 3 (2018), p. 77.

31 The Muʾassasat Āl al-Bayt catalog of Ḥadīth manuscripts lists 2327 manuscripts of the Ṣaḥīḥ that were written in various periods of history and are located in libraries throughout the world. See al-Fahras al-Shāmil li al-Turāth al-ʿArabī al-Islāmī al-Makhṭūṭ, pp. 484-565.

32 Muḥammad ʿĪṣām al-Ḥusaynī provides the biographies of nearly 400 scholars who wrote commentaries, glosses, or related works on the Ṣaḥīḥ. See al-Ḥusaynī, Itḥāf al-Qārī bi Maʿrifat Juhūd wa Aʿmāl al-ʿUlamāʾ ʿalā Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, p. 6.

33 See Ibn al-Wazīr, al-ʿAwāṣim wa al-Qawāṣim, vol. 1, pp. 306-7. The author’s summary of these arguments can be found in al-Rawḍ al-Bāsim, p. 19 ff.

34 Under the entry of ʿAbd Allah ibn Abī Bakr, he alludes to the incident of the migration when ʿAbd Allah would visit the Prophet and Abū Bakr in the cave of Thawr. He then writes that he explained this in “al-Musnad.” Bearing in mind that Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī bears al-Musnad in its title and that the incident in reference is cited in the Ṣaḥīḥ (no. 3905/5807), here al-Bukhārī is referring to his Ṣaḥīḥ. There is a possibility that he is referring to his other book entitled al-Musnad al-Kabīr. See al-Bukhārī, al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr, vol. 5, p. 2, no. 3. He also makes references to his other works. See al-Bukhārī, al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr, vol. 7, p. 87, no. 387/vol. 2, p. 60, no. 1683; ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Shāyiʿ, al-Aḥādīth allatī Qāl fīhā al-Imām al-Bukhārī lā Yutābaʿ ʿalayhi fi al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr, pp. 21-22.

35 Al-Tirmidhī mentions in reference to a particular chain of transmission that “He [al-Bukhārī] included it in his Kitāb al-Jāmiʿ” which is the earliest contemporaneous mention of al-Bukhārī’s Ṣaḥīḥ. See al-Tirmidhī, al-Sunan, vol. 1, p. 70, no. 17; Brown, The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim, p. 96.

36 See al-Suyūṭī, Tadrīb al-Rāwī, vol. 4, p. 338.

37 On the scholarly debate surrounding the usage of wijādah, see al-Baghdādī, al-Kifāyah, pp. 352-54; al-Suyūṭī, Tadrīb al-Rāwī, vol. 4, p. 344.

38 Shaykh Ḥamzah al-Malibārī distinguishes between what he terms “the phase of transmission” and “the post-transmission phase.” The phase of transmission began in the era of the Companions and ended roughly at the end of the 5th century (with al-Bayhaqī [d. 458 AH]), after which the post-transmission phase commenced. He states the early scholars (mutaqaddimūn) are the Ḥadīth experts of the first phase, particularly the skilled among them, and the latter-day scholars (mutaʾakhkhirūn) are those from the second phase. The most salient feature of the first phase is that ḥadīths were transmitted therein via direct chains of transmission whereas in the subsequent phase reliance was predominantly on earlier written works. See al-Malibārī, Naẓarāt Jadīdah fī ʿUlūm al-Ḥadīth, pp. 13-16; idem, al-Muwāzanah bayn al-Mutaqaddimīn wa al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn, pp. 57-62.

39 It is difficult to pinpoint an exact date for this phenomenon; consequently, opinions vary in this regard. Abū ʿAmr Ibn al-Murābiṭ (d. 752 AH) states, “[Prophetic] Reports have already been compiled, and narrator-criticism no longer serves its purpose. In fact, it ceased at the close of the 4th century.” See al-Sakhāwī, Fatḥ al-Mughīth, vol. 4, p. 445. Shaykh Ḥātim al-ʿAwnī opines that all ḥadīths were recorded arguably by the close of the 3rd century, and unquestionably by the 4th century. See al-ʿAwnī, al-Manhaj al-Muqtaraḥ, pp. 52, 61.

40 Al-Bayhaqī, Manāqib al-Shāfiʿī, vol. 2, p. 321; Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ, Maʿrifat Anwāʿ ʿIlm al-Ḥadīth, p. 121. For similar remarks, see Ibn al-Jawzī, al-Mawḍūʿāt, vol. 1, p. 99; al-Zaylaʿī, Naṣb al-Rāyah, vol. 1, p. 335 [summary of Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī’s treatise]; al-Rāzī, al-Maḥsūl, vol. 4, p. 299.

41 Al-Bayhaqī, Manāqib al-Shāfiʿī, vol. 2, p. 321; Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ, Maʿrifat Anwāʿ ʿIlm al-Ḥadīth, p. 17; Davidson, Carrying on the Tradition, pp. 28-33.

42 Ibn Nuqṭah, al-Taqyīd, vol. 1, p. 328; Davidson, Carrying on the Tradition, pp. 92-94.

43 Al-Suyūṭī, Tadrīb al-Rāwī, vol. 2, pp. 561-63/vol. 4, p. 338.

44 Abd-Allah, Mālik and Medina, p. 56.

45 Al-Baghdādī, al-Kifāyah, p. 257.

46 Ibn Kathīr, al-Bāʿith al-Ḥathīth, p. 140.

47 Al-Dhahabī, Mizān al-Iʿtidāl, vol. 3, p. 467; idem, Siyar, vol. 16, p. 389; Ibn Rajab, Dhayl Ṭabaqāt al-Ḥanābilah, vol. 3, p. 320; Davidson, Carrying on the Tradition, p. 95.

48 Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ, Maʿrifat Anwāʿ ʿIlm al-Ḥadīth, p. 180.

49 Ibn al-Wazīr, al-ʿAwāṣim wa al-Qawāṣim, vol. 1, pp. 332-35; al-ʿAwnī, al-Mursal al-Khafī, pp. 880-81. Shaykh Ḥātim further explains there is no reason to distinguish between transmission and practice. See op. cit., p. 882.

50 Al-Ṣanʿānī, al-Muṣannaf, no. 17698.

51 Al-Fasawī, al-Maʿrifah wa al-Tārīkh, vol. 2, p. 217.

52 Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr writes, “The consensus of scholars from all regions upon the dictates of ʿAmr ibn Ḥazm’s ḥadīth is a clear proof of its authenticity.” See Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr, al-Istidhkār, vol. 8, p. 37.

53 Ṣubḥī, ʿUlūm al-Ḥadīth wa Muṣṭalaḥuh, pp. 102; cf. Kamali, A Text Book of Ḥadīth Studies, p. 21.

54 Al-Dhahabī writes, “The criticism of some scholars that these [the ḥadīths of ʿAmr ibn Shuʿayb—his father—his grandfather] are in the form of ṣaḥifah, whose transmission is via non-oral wijādah, is from the perspective that interpolations can creep into ṣaḥīfahs, particularly in that era because there were no vowel marks or diacritics as opposed to studying directly from teachers.” See al-Dhahabī, Siyar, vol. 5, p. 174.

55 Ṣubḥī, ʿUlūm al-Ḥadīth wa Muṣṭalaḥuh, p. 103. On the process of verifying and preparing a manuscript for print, see ʿAbd al-Salām Hārūn’s Taḥqīq al-Nuṣūṣ wa Nashruhā.

56 Personal communication, March 11, 2018.

57 Published as “Riwāyāt al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ wa Nusakhuhu: Dirāsah Naẓariyyah Taṭbīqiyyah.”

58 Ibn Ḥajar, Fatḥ al-Bārī, vol. 1, pp. 5-7; idem, Taghlīq al-Taʿlīq, vol. 5, pp. 444-46; idem, al-Muʿjam al-Mufahras, pp. 25-27.

59 Muḥammad ibn Ṭahir al-Maqdisī (d. 507 AH) mentions the name of Ṭāhir al-Nasafī among the direct transmitters of the Ṣaḥīḥ. See Ibn Nuqṭah, al-Taqyīd, p. 31. Ibn Ḥajar explains that the recension of Abū ʿAbd Allah al-Mahāmilī (d. 320 AH) from al-Bukhārī is an error. See Ibn Ḥajar, Fatḥ al-Bārī, vol. 1, p. 5; idem, Lisān al-Mīzān, vol. 5, p. 667. Aḥmad Fāris al-Sallūm mentions the names of two more transmitters, Ḥashid ibn Ismāʿīl and Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī al-Jurjānī. See al-Sallūm, “Introduction,” in al-Mukhtaṣar al-Naṣīḥ, pp. 42-45. He bases the inclusion of Ḥāshid on a statement of Ibn Ḥajar (Fatḥ al-Bārī, vol. 10, p. 234), but in a subsequent article, he retracted this claim. See al-Salūm, Risālah fī Radd Shubah Minjānā, p. 5. The inclusion of Abū al-Ḥasan al-Jurjānī also seems to be an error. Al-Sallūm cites Ibn Nuqṭah’s al-Taqyīd as a reference, but the passage in question states that al-Jurjānī was a transmitter from al-Firabrī, not a direct transmitter from al-Bukhārī. Ibn Nuqṭah writes, “In his book, Muḥammad ibn Ṭāhir states, ‘A group of people narrated Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī from al-Firabrī. Among them were Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥamawī, Abū Isḥāq al-Mustamlī, Abū Saʿīd Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Rumayḥ, Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Jurjānī, and Abū al-Haytham Muḥammad ibn al-Makkī al-Kushmīhanī.’” See Ibn Nuqṭah, al-Taqyīd, p. 11. Given that al-Jurjānī passed away in the year 366 AH, it is far-fetched that he transmitted directly from al-Bukhārī. See al-Dhahabī, Siyar, vol. 16, p. 247.

60 Jumuʿah, Riwāyāt, pp. 203-205.

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this paper!