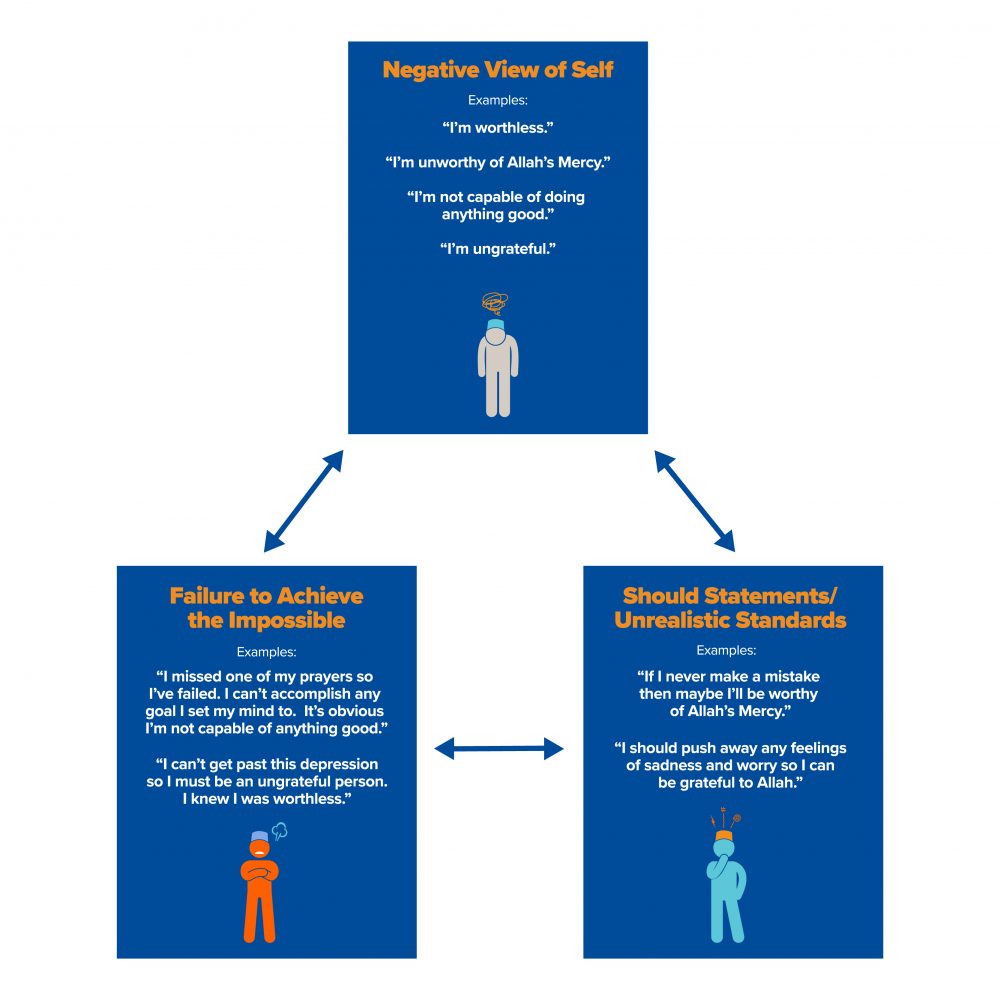

If you are feeling as though your emotions indicate that you aren’t a good Muslim, that thought can be changed. Let’s consider the trajectory this thought pattern might lead to:

“I shouldn’t be feeling sad. My iman must not be strong enough.”

↓

“If I have weak iman, then my relationship with Allah is weak.”

↓

“If my relationship with Allah is weak, then Allah must be upset with me.”

↓

“If Allah is upset with me and hates me, then I must be doomed.”

↓

“If I’m doomed, what’s the point in trying to change things?”

Here, we see the connection between emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. When we are in pain and we set unrealistic standards about overcoming these emotions, these unhealthy thoughts propel us into a hurtful cycle. These negative thoughts lead to negative emotions, which eventually yield negative behaviors.

If you or others around you are enforcing a set image of what it means to be a good Muslim and this image involves not grieving or allowing yourself to feel uncomfortable emotions, you may start to expect that Allah wants the impossible from you. And if you can’t fulfill the impossible, what’s the point of trying? This can have a profound impact on our relationship with Allah.

You can find some helpful definitions below.

Please note: A lot of Islamic literature utilizes the words “guilt” and “shame” interchangeably. It is difficult to translate Arabic terminologies directly into English so although some Islamic publications may describe shame as a positive attribute, the way the author is typically defining this concept is in line with the definition of healthy guilt below. Whatever terminology is used, our main goal is to propel ourselves forward in strengthening our connection with Allah (swt) versus holding on to an emotional experience that pushes us further away from Him.Healthy guilt is a feeling of psychological discomfort about something we’ve done that is not in line with our personal values. We can use this to hold ourselves accountable and work toward positive changes. The key here is identifying the

behavior as inappropriate, rather than identifying

yourself, as a person, as the problem. Healthy guilt is similar to what

the Prophet ﷺ described when he said, “Consult your heart. Righteousness is that about which the soul feels at ease and the heart feels tranquil. And wrongdoing is that which wavers in the soul and causes uneasiness in the chest, even though people have repeatedly given their legal opinion [in its favor].” Unhealthy guilt is a feeling of disproportionate psychological discomfort about something we’ve done against our irrationally high standards. This could be about something sinful or something completely benign like asking someone for help.

Shame is an intensely painful feeling of being fundamentally flawed. We feel this because we see ourselves as unworthy and deeply flawed.

Consider the different implications of these statements:

Healthy guilt: I’ve been feeling so down lately that I’ve been struggling to pray. I feel like it’s taking a toll on my relationship with Allah so I’m going to pray at least one prayer today since I know this is an obligation and I can feel good about fulfilling an obligation to Allah.

Unhealthy guilt: I’ve been feeling so down lately that I’ve been struggling to pray. I should be able to do it all perfectly and if I can’t do it all perfectly, there’s no point in doing anything at all. If I can’t keep up with all my prayers, there mustn’t be any hope so I won’t bother doing any of them.

Shame: I’ve been feeling so down lately that I’ve been struggling to pray. Allah must hate me since I can’t do anything right since I can’t even keep up with simple things. I must be a worthless person and a waste of space in the world.

A balanced, healthy feeling of guilt is an asset for us to be able to hold ourselves accountable.

‘Umar ibn al-Khattab said, “Call your souls to account before you are called to account and weigh your souls (actions) before you are weighed, for it will make the accountability easier for you tomorrow if you call yourselves to account today.” Healthy guilt functions as a compass for our hearts and minds.Furthermore, healthy guilt reminds us of the benefits of repentance following a questionable choice we’ve made. Allah says in Surah az-Zumar,

“Say: ‘O My slaves who have transgressed against themselves! Despair not of the Mercy of Allah, verily Allah forgives all sins. Truly, He is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful.” Here, we see a promise that Allah (swt) forgives every sin and that we are commanded to never despair of His Mercy. He does not expect perfection from us. He reminds us that things are not hopeless and that He believes us to be worthy of His Forgiveness even if we struggle to forgive ourselves.While being human necessitates imperfection, it is incredibly liberating to realize that it is not so much about our sins or our good deeds, but rather it is fundamentally about Who Allah is. We are hopeful, not because our shortcomings are small, but because Allah’s Mercy is so great. And we are hopeful, not because our repentance is so sincere that we deserve forgiveness, but because Allah’s Compassion is so vast and His Promise of forgiveness is true. Sometimes overemphasis on our mistakes causes us to forget the Magnificence and Mercy of the One who has promised to forgive these same mistakes when we sincerely turn to Him.

Ask yourself these questions as you try to dismantle your “should” statements:

What rule or assumption are you struggling with right now?

Example: I believe that my feelings of sadness mean that I must have weak iman.

How does it affect your daily life?

Example: I feel ashamed to ask Allah for help because I’m not good enough to deserve it. I can’t pray anymore because I feel worthless in the eyes of Allah and no matter what I do, I don’t think it will ever be enough.

When did you first realize that this unspoken rule became a part of your life? How did you learn about it? What was happening when you first adopted it?

Example: When I was younger, I was always told that Muslims never feel sad because they are always grateful to Allah, no matter what happens. My Sunday school teachers told me, “Iman and sadness cannot coexist in one heart.” So, when I felt sad, I assumed my iman disappeared.

What are some of the advantages of this assumption? What are some of the disadvantages? (How does believing this “should” statement help you and how does it hurt you?)

Example: Sometimes thinking this way pushes me to pray more, fast more, and read more Qur’an but I always end up going backward after a little while. Believing that my negative feelings mean that I have weak iman usually leads me to stop praying and stop making du’aa because I don’t feel like I’m worthy of being heard by Allah.

What is a potential alternative rule/assumption/statement that would better suit you?

Example: Allah created us with emotions for a purpose. Feelings of sadness are normal and acceptable. My emotional state does not define my spiritual relationship with Allah (swt) nor my ability to worship Him.

How can you put this new and improved rule into practice in your daily life?

Example: I can remind myself that the Prophets عليهم السلام all experienced difficult emotions and Allah loved them; therefore I can be loved by Allah too. I can still be close to Allah even when experiencing feelings of sadness.

It can be a struggle to move past the negativity you’re experiencing—so much so that you may begin defining yourself based on your struggles. Consider how you want to be defined. Do you want to define your relationship with Allah based on your current struggle or based on the potential closeness you can strive toward? Your relationship with Allah does not need to be defined by how you are feeling right at this moment.

We often identify with our imperfections and the negative occurrences that surround us rather than focusing on our positive qualities and the things that are going right in our lives. Trials afflict good people too. And doubts, dips in iman, and negative thoughts affect good people as well. Don’t let the things that are going wrong define you. Never believe that you are beyond forgiveness; never underestimate the Mercy of Allah. Allah sees you and knows your heart, mind, and circumstances better than you know them yourself. He knows your struggles. Allow your positive choices moving forward to define you and to define your relationship with Allah.